- Home

- Sullivan, Luke

Thirty Rooms To Hide In Page 2

Thirty Rooms To Hide In Read online

Page 2

40 years later, my mother is still grieves the final years of her husband’s life. She won’t admit this, but I think she does. She won’t talk about the old days without being asked and then her answers are short. “Why do you want to know such horrible things?” It almost seems to offend her, like I’m some reporter shoving a mike in her face. But she says she’s willing to try.

“This remembering you’re asking me to do isn’t going to be easy,” she admits. “Worse, it may not even be fair. The chance to get even by painting him meaner than he actually was will be tempting. He’ll just have to take the chance that maybe he blew all hope of being remembered fairly.”

There is some anger in her voice today. There is regret, too. And, strangely, some shame.

“I hate that something so ordinary happened to my marriage.”

She says ordinary because what happened to her husband and to her family seems like a soap opera now. The shame is harder to understand. Perhaps she thinks she could’ve stopped it from happening; not one of us six boys sees how, but she feels it nevertheless.

From her shelves, I bring down a scrapbook she made for Roger in 1945, right after they married. It’s the story of their courtship written as a keepsake for her new husband and it’s the first time I’ve ever seen it. It’s full of ticket stubs from ancient movies, matchbooks from restaurants long closed, hand drawings by an effervescent 22-year-old girl, and the whole thing smells like it’s spent a lot of time in a trunk.

She cringes at some of the writing. “Embarrassing!” she says turning a page. “That letter was pretentious. Straining for effect.”

“But I was only 22”, she softens. “I was probably trying to sound grown-up and judicious for my folks.”

She turns to her desk and fiddles with the tape recorder I’ve set up. We’re settling in to talk about the old days and about the girl who made the journal I’m holding.

Paging through this journal, the romance of Roger and Myra seems like an old black-and-white movie. They were two “co-eds” from the 1940s; they went on double dates to football games, met at the library between classes, and had real malteds at real malt shops. He, with his dark Irish good looks and brown eyes for the Florida girl to swim in; she, also dark-haired, short like her father, and a thin waist for the minister’s son to put his arm around.

I press RECORD and my mother begins to talk about the co-eds and how they came to live with six sons in a house with 30 rooms called The Millstone.

Dad (right) and a colleague.

BONE DOCTORS

“He wanted to be the next Albert Schweitzer.” Mom says, sitting now with a fresh cup of coffee. “He dedicated his career and life to a service so altruistic. He was going to be a medical missionary.”

She’d met Roger in the fall of 1941 on a blind date at Ohio Wesleyan College. In the summer of ’43, Roger went on to medical school in Rochester, New York, and Myra joined him there with plans for nursing school. But during her physical exams, Myra was told her x-ray revealed a “scar” on her lung and that it was likely to be tuberculosis. In its day, T.B. was the leading cause of death in the United States. And the cures – in 1943 anyway – included deflating a lung, removing it, or bed rest.

So my mother’s blossoming relationship with Roger – her whole life really – was put on hold and she returned to Florida to spend six months on her back in bed at a sanitarium (or “the San,” as she called it in letters to Roger).

It was with these letters and with “long-distance telephone” they kept alive the flame lit in Ohio; more, my mother says, on her initiative than his. When she finally joined him again in New York, they were married at a ceremony with only themselves and the minister in attendance. Barely a month passed before a follow-up x-ray suggested Myra’s T.B. was not in remission and she went back to the Florida sanitarium, leaving Roger in New York to finish medical school.

So it was that the first year of my mother’s marriage was spent in bed-rest. With her new marriage on pause and her college education on stop, she continued to study, receiving books in the mail from an empathetic Ohio Wesleyan professor. In her bed that year she inhaled prodigious amounts of information, beginning what amounted to a life-long self-guided Ph. D. in English Lit.

The year passed while Roger continued his surgical training on the Navy’s V-12 program at the University of Rochester School of Medicine. Finally in the spring of 1945, with a clean bill of health, Myra joined him there. After graduation she traveled with her young husband to his naval station in Portsmouth, Virginia.

It was here, actually, where Roger and Myra began their American dream. The war in Europe was over. The country was about to coast into a long period of extraordinary prosperity and conservatism and the future for young couples looked bright in a way America would never see bright again. The Baby Boom began, Ground Zero of which will perhaps one day be traced to my parents’ bedroom. In four years, the first three of six sons were born: Kip in 1947, Jeff in ’49, and Chris in ’51 – the second and third, results of leaves of absence from Truman’s Navy.

One year after his honorable discharge Roger landed a residency in orthopedic surgery at the famous Mayo Clinic and the family moved to Rochester, Minnesota. A fourth boy – Dan – was added to the crowded little farmhouse and then the booster rockets of Roger’s medical career kicked in. In January of the year I was born, 1954, Mayo invited my father on to become a full staff member and all the financial benefits that came with it.

* * *

Even today, becoming a staff surgeon at Mayo is a bit like joining a secret society – a “Skull & Bones” with real skulls and real bones. Physicians have always had a mystique, back even to the days of medicine men. Doctors are just different. Their handwriting, a secret code, inscrutable to all but another doctor; their garb, blazing white and with a face mask no less. Few begrudge this breed the salaries they command. There’s even the old joke about the doctor explaining his operating fee of $10,000 and one cent: “The penny’s for the surgery. The ten grand’s for knowing where to cut.”

Doctors do in fact know where to cut and when they speak, we can tell they know because we hear the Voice of Authority. We nod as the doctor quietly tells us things, sometimes horrible things, and we doubt none of it. We nod as we listen in his small examining room, or gather in a clutch outside his swinging emergency room doors. And when one of the chosen speaks – here at the Mayo Clinic – it is with the Highest Authority. This is after all the ivory tower of western medicine, where you have traveled far to hear the Definitive Answer. And as you listen you nod yes.

I can hear this voice of authority today as I step into the parlor of the man who gave my father the job at the Mayo Clinic – Dr. Mark Coventry, chief of its Department of Orthopedics for 19 years. He’s nearly six feet tall and a head of white hair adds to the regal bearing I remember as a child. He’s retired now and, with children scattered across the country, we have the house to ourselves to conduct a sort of post-mortem on his old friend and colleague, Dr. Charles Roger Sullivan.

In a chair in his study, Dr. Coventry (the medical mystique prevents me from calling him “Mark”) has little trouble remembering details about my father.

“He was very good with people – witty, personable, intelligent. His performance was first-class in every way, so we of course asked him to stay on.” In those days, he recalled, “orthopedists did everything. There wasn’t the sub-specialization there is now.”

As I set up my tape recorder, he describes how my father began to specialize in children’s orthopedics.

“I remember your father established a baseline for the curvature of the cervical spine, which was always poorly understood before his clinical research. One paper in particular he wrote on the curvature of the cervical spine in children is still quoted from considerably today.”

There’s pride in hearing that my father was an Authority. I get up to readjust the tape recorder and as I walk back to my seat, the Mayo doctor intones, “How long

have you lived with that limp?”

It’s been two years since I broke my right leg in a trampoline accident –a “comminuted” fracture below the knee that when it happened sounded like a broomstick snapping. It’s precisely the kind of injury which might have been wheeled into Dr. Coventry’s operating room had I been living in Rochester at the time instead of Minneapolis. When I explain I’d successfully completed nearly a year and a half of physical rehab, Dr. Coventry – in the Voice We Nod Yes To – says, “Well, obviously you haven’t isolated the right muscle group and strengthened it.”

He tells me to turn around and walk the length of the room again.

I obey.

When my leg first came out of the cast, I was startled at how the muscles had atrophied; I could almost wrap my hand around my thigh. But the sessions at rehab had brought back the girth and helped me walk again. As I limp back and forth across Dr. Coventry’s living room floor, I tell him the stories about modern knee-replacement surgery I’d heard from the Twin Cities’ doctors; how I’ll be a candidate for a full replacement one day but until then, I inform him, my gait is the best that can be expected.

“The knee may well be replaced but your problem is a muscle in the gluteus group, one you simply haven’t isolated,” says the Voice.

He reaches for a pad of paper and scribbles some of the famous hieroglyphs to pass on to my physical therapists – exercises to identify the weakened muscle. As he does this, he tells me how the joint-replacement surgeries I’d just been kind enough to explain to him were developed by his team at Mayo back in the ‘60s. He tells me how the first hardware was forged, how they began work with polyethylenes, the medical-grade plastics that replaced their patients’ tattered cartilage and how they sank long metal tubes into the middle of femur bones.

As he talks I remember what my father told me when I asked what he did at work. “Well, it’s sort of like carpentry,” my father had said. “You have a saw and a drill and some screws and you make things fit together perfectly and that’s all there is to it.”

This skill – part Grey’s Anatomy, part Black & Decker – fascinated me, as it did my mother. She often described my father’s latest surgery in letters to her parents.

Rog is on emergency this week. Last night he was in O.R. till 2a.m. putting an arm back together that was mangled in a combine. Last week he did a hip pinning and put a “McLaughlin plate” on a woman with an intertrochanteric fracture. Tomorrow Roger must operate on the little daughter of friends of ours. She came in with a lump on her leg near the knee. Roger tried to break it as gently as possible, but had to inform Bill he must biopsy his daughter’s leg tomorrow, not Wednesday. He doesn’t see how it can be anything other than a fibrosarcoma – but he hopes he’s wrong. If he’s not, the child’s leg comes off, mid-thigh. These fibrosarcs are so malignant that even a biopsy is done between tourniquets.

If there’s a day when my father’s skill shone most brightly it was when he operated on a family friend, Richard Plunkett, then president of the Rochester Savings & Loan.

Like many gentlemen farmers living just outside of Rochester, Plunkett kept horses and was a skilled rider. In July of 1963 he was badly injured in a riding accident. When he arrived at the hospital, x-rays showed his pelvic bone was in 17 pieces. Years later, his daughter Pat told me “before they wheeled him into O.R., he was given the Last Rites by a Catholic priest and was whispering to Mom what to do if he didn’t make it.

“It was a long surgery,” Pat remembered. “Your father wired my dad’s whole pelvis back together. Dad still credits your father with his life.”

In 2004, my brother Chris wrote to tell me he’d met an orthopedic surgeon from India at a party. “When I indicated my father had also been one,” Chris wrote, “she asked where he’d practiced. I said the Mayo Clinic and the lights went on in her eyes. She said, ‘Oh, you mean the Dr. Sullivan?’”

The Dr. Sullivan’s career is in fact well documented. In the Plummer Building across from the Clinic is the medical library and in its stacks, his papers; lots of information on him as a surgeon but nothing about him as a man. Before I leave Dr. Coventry’s house, we begin to talk about Roger’s private life; about those insane final weeks of June, ‘66.

“Perhaps you ought to contact the facility he was treated in,” he suggests. “The man who was running it had been the head of our staff in psychiatry, Dr. Braceland.”

I told him I’d already been in contact with the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut. There are many strange things you can order over the phone and your deceased father’s 40-year-old psychiatric records are right up there. (The strangest is ordering a police report on the scene of a death. “Um, yes, my father kicked the bucket in a motel in your precinct back in ‘66 and… um, University Motel, I think. … Yes, I’ll hold.” Followed by: “Moon Riverrrrr, wider than a mile….”)

But Dr. Coventry knows plenty about the insanity. It was he who’d driven out to the Millstone to calm my father down on nights when his rage scared Mom enough to call for help. It was he who’d tried to keep my father from resigning so we wouldn’t lose his family benefits and medical coverage. And it was he who drove to our house that Sunday morning to bring my mother the news of his death.

At the door, I ask him if he thought the death of Roger’s mother six months prior to his own demise had anything to do with his final dissolution. The dry conclusion given by the Mayo physician is, again, the Definitive Answer.

“No. There’s always something in life. You’re never going to be free of those things. Roger simply couldn’t handle his problem,” said the doctor.

I nod yes.

The Rock, 1960

GRANDMA ROCK SENTENCES EVERYBODY TO HELL

For many years after our father’s death my brothers and I unfairly laid all the blame for Dad’s low self-esteem squarely in the frosty Puritan lap of his mother, Irene.

H.L. Mencken described Puritanism as “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, might be having a good time.” Irene rarely seemed to be having one and certainly nobody standing near her did. She was a chilly woman who banged the Bible more than she did her husband, shamed her only child at every opportunity, and sucked all sense of hope and joy out of every room she ever entered. Hugging her was like putting your arms around a burlap bag filled with sticks; she didn’t hug back either. Nor did she laugh. Nor ever use the word “love” that didn’t have the word “Jesus” in the same sentence.

If she’s in hell now, she’s the librarian.

She was cold like a rock and so we six boys nicknamed her “Grandma Rock.”

Her husband was a Methodist minister but none of us knew Grandpa Sullivan; he died in 1942. Later we became convinced he died early just to ditch Irene earth-side and get a head start into eternity. The six boys and Mom weren’t the only ones who didn’t like Grandma Rock; even Dad finally admitted to it, though privately. A year before he died, he confessed to his psychiatrist that while he’d at least liked his father, his mother was a different story.

The patient said at this juncture, “I don’t like my mother, as you can see from my scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.” He went on to describe her as “a farm girl who taught school and married when she was 31 years old.” [Pressed for more,] he said she’s “good about church-going.”

“Good about church going”? If you were to ask any of Roger’s sons about their mother, we’d say: “Loving. Encouraging. Smart. Funny.” The best my dad could manage was the less-than-stellar “Good about church-going.” (“Bob Eubanks? I’ll take Bachelorette Number 3! Because she’s ‘GOOD ABOUT CHURCH GOING!’”) Roger’s other memories of life in Irene’s household were equally effusive: “We always had enough to eat” perhaps being his most ringing endorsement.

The patient remembers his mother as stern, rigid, and recalls guilt feelings concerning his pursuit of sexual information. He traced a history of being an only child who never felt close to his parents. Above all, th

e patient remembers a stern, religious environment in his childhood home. On one occasion when he was at a church summer camp, he recalls the atmosphere of the “old-time religious environment” got to him. He recalls crying and going to the altar in response to the evangelist’s plea. On the way home that night, he clearly remembers his mother’s disapproval and his feeling of resentment.

Grandma Rock offered her son a rancid little cup of her religion and when he moved to drink from it, she shamed him – “for drawing attention to yourself walking up to the front of the church like that.”

There are pictures of our father growing up in this religious meat locker and in all of them he looks haunted. Standing there next to his prim mother, his eyes have that same look the prisoners-of-war had at the Hanoi Hilton press conference, blinking Morse code to the photographers. (“Am being tortured. Forced to stand next to her. Send help.”)

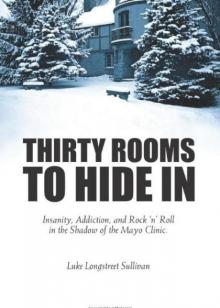

Thirty Rooms To Hide In

Thirty Rooms To Hide In